Union Square

Union Square Neighborhood Association

Hollins Market Neighborhood Assocation

- Baltimore City Historic District Ordinance 821 6/2/70; 580 11/17/77

- Certified Historic District for Tax Incentives 6/9/80

- National Register of Historic Places 9/15/83

Summary Description

The Union Square local historic district is a dense area of rowhouses and commercial structures located in Southwest Baltimore. Two major features define the district: Union Square Park, a donation to the city in the 1840s, and Hollins Market in the city’s oldest market building. Generally bounded by South Schroeder, West Pratt, South Fulton, and West Baltimore Streets, the area of approximately 21 blocks is comprised of over 1,000 buildings. The district is built on a street-grid system laid down over gently sloping terrain by engineer-surveyor Thomas H. Poppleton following the land’s 1816 annexation to the city.

The Poppleton Plan affected street widths and lot sizes, in turn creating a hierarchy of building sizes and locations, and determining the socio-economic levels of who lived where. The result is still very much in evidence today. Modestly scaled housing for workers is found on side streets and alleys. Built on narrow lots beginning in the 1830s with two to two-and-a-half stories and side gables, the buildings later evolved into two-story-and-attic houses in the late 1840s and 1850s. They accommodated the Irish and German immigrant populations that responded to the needs of the burgeoning railway, iron and other heavy industry nearby. Larger, wider and more elaborate three-story three-bay red brick townhouses can be seen lining Union Square Park as well as Hollins and Lombard Streets. The Italianate style predominated when construction was at its height in the mid to late 19th century. Wood, stone or iron window hoods, arched door surrounds, continuous cornices of wood or metal, marble stairs and ironwork at windows are characteristic features from this period. Commercial structures are found around Hollins Market and along South Carrollton Street, with larger scale late 19th century commercial buildings along West Baltimore Street. While the district is significantly intact, gaps in the streetscape from demolitions, especially along West Baltimore are evident.

Larger historic institutional structures in the Union Square district in addition to the Hollins Market include a number of churches, along with buildings formerly housing a free library, a police station and a fire station.

History/Summary Significance

In the late 18th century the area west of Baltimore’s original core around the Inner Harbor contained large tracts of woodlands and farms. Willow Brook, the 1799 country estate of Thorowgood Smith, merchant and Baltimore’s second mayor (1804-1808), was comprised of 26 acres with its Federal-style house standing on the site of today’s Steuart Hill Academic Academy on the west side of Union Square Park. Smith ceded the estate to his niece’s husband John Donnell after financial reversals.

Physical Development

With the opening of the Baltimore-Frederick Turnpike in 1807 and the city’s annexation of this area in 1816, development proceeded to push westward, and the land began to be converted to dense residential, commercial and industrial uses. The character of the development was influenced by the street plan of surveyor Thomas Poppleton who was engaged shortly after the city’s annexation of the land. His plan, published in 1823, overlayed the terrain with a grid containing a hierarchy of streets. From high to low in importance, the order was: east-west streets, north-south streets, and alley streets. This resulted in lot and building sizes that determined the housing locations of individuals by socio-economic standing.

The establishment in the early 1830s of the B & O Railroad’s Mount Clare yards, the Bartlett-Hayward foundry, and Winans locomotive works along and south of West Pratt Street created a need for inexpensive housing for factory workers. This need was met nearby with the construction of small modest houses on the alleys or side streets created as a result of the Poppleton Plan. Because of transportation constraints, people of all classes lived relatively close to one another—and to their work. Hollins Market, opened in 1838 on land donated by George Dunbar, another early land owner and banker, helped meet the needs of the growing populace.

In 1846 John Donnell ceded one square of his land to the city for use as a public park bounded by Hollins, Stricker, Lombard and Gilmor, a public gesture that was also tied to private real estate speculation. By 1852 a fountain, a pavilion over a natural spring, and a cast iron fence had been added to the park. By 1869 high style rowhouses filled the east side of the square and several of the corners had buildings. Along the wider more traveled streets in the rest of the area, larger high-style rowhouses and commercial buildings were constructed at an increasing rate after the Civil War. While the residential sections of the street grid in the entire Union Square district were essentially built out by about 1880, construction of institutions and commercial buildings continued into the early 20th Century.

Social and Cultural History

The character of the district is tightly linked with its early 19th century associations with the heavy industries that bordered the Union Square neighborhood to the south. The establishment of the B & O Mount Clare Yards (referencing the 18th century Charles Carroll plantation, Mount Clare, which survives nearby) fueled the development of other new heavy industrial operations. The need for workers and the constraints on transportation spurred the building of worker housing nearby on the recently opened streets in the new expanses that would become the Union Square district. Workers came from Ireland and Germany, bringing their customs and culture with them.

As a neighborhood, the area prospered through the rest of the 19th Century as seen by the commercial development growing along West Baltimore Street and around Hollins Market. Decline set in in the 20th century as major employers of area residents, such as the B & O shops and Bartlett-Hayward shut their doors. Following the Depression and World War II the area continued to struggle. Federal housing policy and accompanying auto-centered development encouraged and enabled families—predominantly white—to leave urban centers in the 1950s and 1960s. In turn, federal urban renewal policies focused on the resultant conditions of old city cores. In Union Square beginning in the 1960s private and public efforts began to focus on reviving the neighborhood. The two landmarks that define the district, Union Square Park and Hollins Market were rehabilitated in the 1970s. Focusing on revitalizing the commercial character of West Baltimore Street, the City initiated a “Shopsteading” program similar to its Homesteading program, to encourage business development in vacant structures. The area immediately surrounding Union Square Park became a local historic district in 1970 and in 1977 was expanded to its current boundaries.

The neighborhood today continues to reflect the dynamic forces that play out in contemporary urban neighborhoods facing continuous challenges and economic shifts. While the majority of Union Square’s built environment has remained intact, many buildings have been lost in the last few decades, especially along West Baltimore Street. Most notable are the 1000, 1200, 1300, 1600, and 1700 blocks.

Union Square was the home of journalist and social critic H. L. Mencken for most of his life, and many leading figures of the era called on him there. His father brought the family to 1524 Hollins Street in 1883. Mencken died there in 1956. Writer Russell Baker lived across Union Square from Mencken on West Lombard Street when his family first moved to Baltimore in the 1930s. Writer Dashiell Hammett lived just north of Union Square near Franklin Square as a child, and frequented Union Square’s Free Library Branch on Hollins Street.

Architecture

The earliest building associated with Union Square, Willow Brook, the 1799 Federal-style manor house, became a school for young girls run by the Catholic Church in 1864. The interior featured one of the finest Adam-style rooms in the country, an oval salon. The original house underwent a number of additions over time, essentially disappearing under the alterations. When the building was demolished in 1965, the salon was preserved in the Baltimore Museum of Art. The Steuart Hill Academic Academy occupies the site today on the west side of Union Square Park.

The Federal style was typical for structures built in Union Square in the early 1830s: two-bay two-story houses with a central dormer and steep side gables. The facades are of Flemish bond brick with corbeled brick cornices. A few examples remain scattered in the district including on West Baltimore Street. In the 1840s and 1850s, Greek Revival was popular, with houses replacing dormers with attic windows, roof pitches becoming shallower, common bond brick replacing Flemish bond, and cornices containing modillion blocks. These can be found in the Hollins Market area. Each of these two styles was relatively restrained and free of ornament.

The Italianate style, which is seen in the greatest number in the district, was popular in the period of Union Square’s fastest growth and development from the mid-1850s to the early 1880s. The buildings have a full third floor, sometimes a third bay, a shallow roof that slopes to the rear behind a cornice decorated with brackets, scroll work, dentils and modillions. Windows are four-over- four or two- over- two double-hung. Lintels and subsills are of stone. Brick is factory pressed laid in running bond; bases and steps are marble or brownstone. Continuous, intact rows of Italianate style houses can be found in the western half of the district on Hollins and Lombard Streets, with some of the most elaborate on the west side of Union Square Park. Some of the latter buildings have cast iron or wooden hoods over the windows or doors, round arched doors with molded surrounds, elaborate cornices with dentils, and egg and dart motifs, wrought iron grills, and fences setting off tiny front gardens.

Smaller versions of these styles were built on the alley streets, usually no more than two stories high, with less ornament and a reduced floor plan.

Commercial architecture, especially along West Baltimore, is mostly in the Italianate style with larger structures also in the Renaissance Revival and Neo-Classical Revival styles.

The district contains a number of architecturally significant institutional structures and churches including the Italianate Hollins Market (1864); Enoch Pratt Free Library (1883), the Colonial Revival former Southwestern District Police Station (1884), Germanic Romanesque Revival former Fourteen Holy Martyrs Church/Praise Cathedral (1902), former Fulton Avenue Baptist Church/Divine Mission (1880s), the Union Square Methodist Church (1853-55), Fourteen Holy Martyrs School and Hall (1928), and a Neo-Classical Revival former city fire station (1902).

Period of Significance

The two buildings at 1412 and 1504 West Baltimore may date to the 1820s, making them the oldest in the district. The latter, associated with Malachi Mills, a free African American carpenter, may be the only frame house in the district. A handful of buildings possibly dating to the 1830s survive. The vast majority of extant residential structures in the Union Square district date to the period 1845-1880, with institutional and commercial buildings continuing to be added in the late 19th and into the 20th Century. The period of significance of 1820 to 1930 encompasses the range and location of housing for residents of a variety of socioeconomic circumstances, and the institutions and businesses that served them. In addition the period captures the eras of Baltimore’s growth as it expanded from its original core around the Inner Harbor into formerly open spaces, transforming them into dense urban neighborhoods adjacent to burgeoning industries.

Boundaries

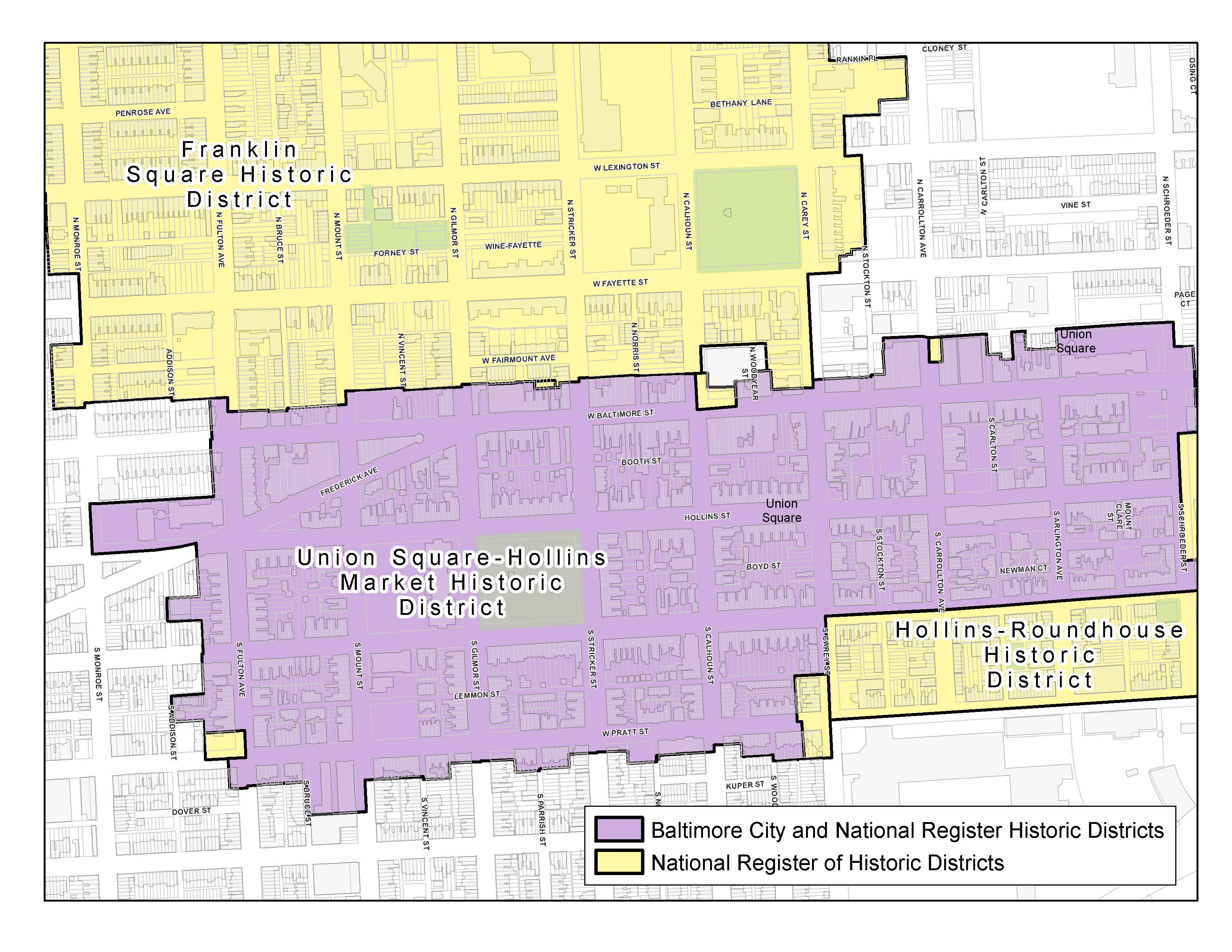

The Union Square local historic district is generally bounded by South Schroeder Street; West Lombard Street from Schroeder to Carey Street; the rear property lines of buildings on the south side of West Pratt; the rear property lines of properties on the west side of South Fulton Street; and the rear property lines of buildings on the north side of West Baltimore Street. This captures the two key community anchors of the district—Hollins Market and Union Square Park—and reflects the related physical, social and cultural history of this section of the City of Baltimore.

References

City of Baltimore Department of Housing and Community Development, Impact of Expanding the Boundaries of Union Square Historical and Preservation District, 1977

Hayward, Mary Ellen and Frank R. Shivers, Jr. The Architecture of Baltimore: An Illustrated History, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Maryland Historical Trust. National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form—Union Square/Hollins Market Historic District, 1983.

Olson, Sherry H. Baltimore: The Building of an American City, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Sanborn Map Company, Baltimore, Maryland: Vol. 1 & 2, 1914, Republished 1953, “Digital Maps 1867-1970” <http://sanborn.umi.com/md/3573/dateid-000036.htm?CCSI=2043n> (Accessed July 14, 2016).

Stanton, Phoebe B. Poppleton Historic Study, City of Baltimore Department of Housing and Community Development, 1975.

University of Baltimore School of Communications Design. The Baltimore Literary Heritage Project <http://baltimoreauthors.ubalt.edu> (Accessed July 7, 2016).